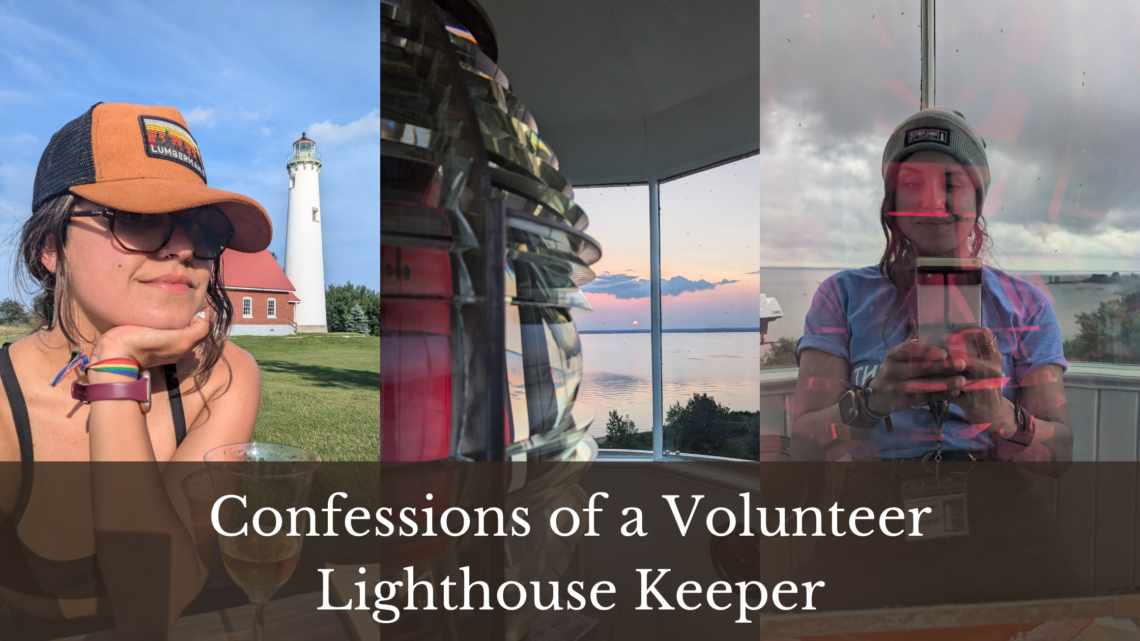

Confessions of a Volunteer Lighthouse Keeper: Tawas Point 2024

I kept and broke a lot of rules this summer, including some of the rules I had while being a volunteer lighthouse keeper at Tawas Point Lighthouse in Michigan. For example, we forgot to take down the flag one night, which we were supposed to raise and lower every day, and sometimes we let people in flip flops climb the tower even though we weren’t supposed to.

One time I even gave a kid an “I CLIMBED TAWAS POINT LIGHTHOUSE” button even though his parents hadn’t made a donation. But he was scared about making the climb back down the tower and giving him the button totally worked. I told him everyone who saw him wearing it would instantly know how cool and brave he was. He grinned and finally took his mom’s hand to start the descent, the button pinned on his chest.

I think it’s okay to break most rules. Everyone should probably practice breaking at least one rule a day. Not anything too serious. Just something to remember how none of us chose to be here (on Earth, I mean) and we should get to do what we want sometimes.

That’s something I thought a lot about on my Michigan trip this past July, especially after I was too honest about what I had in my fanny pack at the Canadian border. My group was detained for twenty minutes because I couldn’t lie like a normal person. They would’ve just waved us through, but no, I had to compulsively confess like the very good girl I was raised to be. (Everyone should practice telling one lie a day too. It can even count as breaking a rule.)

We still got our passport stamps, though, which was all we cared about anyway, and on our drive to breakfast back in Detroit, I noticed that my only other stamp was dated exactly a year before, to the day. I’d gotten it at the Dublin airport.

Working on this essay, I’ve thought a lot about rule-breaking and coincidence, finding patterns in life and wringing them for meaning, or breaking away from pattern to carve out my own deviations. These are the themes I’ve tried to connect to the details from my trip. It’s turning into a whole thing and I’m not done writing it yet, but I wanted to share some excerpts so I still make my goal of posting to my blog every month.

I’ve pulled a little from each vignette I’ve written so far, to give a glimpse into each story.

Excerpt #1

The closing credits of Butterfly in the Sky started almost the moment it was time to deplane at my destination, after the stop-and-go interruptions of cabin announcements, and I injected a little magic and purpose into my travel-amped body by pretending it was kismet. Why not? I was supposed to see this show, in its entirety, at this moment, en route to experiences I was additionally determined to make meaning of:

- Three nights in the Upper Peninsula,

- two weeks living in a lighthouse in East Tawas, and

- three nights in Detroit.

It would be my first time in all three places, first time in a lighthouse, and first time in Michigan.

Excerpt #2

I learned a little about a lot of topics at the lighthouse in the course of talking to guests and studying from the materials the program had provided, but I made lens-facts my go-to conversation filler with guests.

On tower duty, when I’d sit in the lantern room with the lens and talk to the climbers who made it up the 85 steps to see the view, I’d point out the size of our 4th order fresnel lens (about two feet in height and width) and say, “The fresnel lens was invented by a French physicist named Augustin Fresnel. This one is a 4th order lens, which means it’s the 4th biggest kind of lens. Guess how big a 1st order lens is!” Pause for guess. “It’s 12 feet tall and 6 feet wide! Your dad could jump around in there!” Pause for Oooos. “Want to make a donation for a button?”

At the top and bottom of the tower there were donation boxes with a suggested donation of $1 in exchange for a TAWAS POINT LIGHTHOUSE bracelet or a pin-on button with an image of the lighthouse and the words I CLIMBED TAWAS POINT LIGHTHOUSE.

Back at the Michigan Science Center, I stared hypnotized at Leon Foucault’s pendulum for several minutes.

Who knew French physicists would feature so prominently in my summer?

Excerpt #3

The donations we collected went to the nonprofit that helped run the Lighthouse Keeper Program: the Friends of Tawas Point, a group of “spunky” senior citizens who seemed to have a frictious relationship at least with the legitimate historian who directed the program. I’ll call her Mary.

Mary conducted our initial orientation and training sessions after we were accepted into the program, and talked about “the Friends” in the euphemized language of someone secretly itching to say outright, “I can’t stand these women.”

In our first training session, Mary also mentioned that Tawas Point had been closed last year for restoration. As program volunteers, we’d need to be ready for “a lot of pent up lighthouse desire” from the public.

It was a phrase I rolled gleefully around my head for the many weeks between our getting accepted into the program and reporting to our first day on duty: Pent up lighthouse desire.

Excerpt #4

I don’t accept any obligation to the coincidences of my life, and I’m instinctually suspicious of dogmatic explanations for the “miraculous” that imply a worthiness quotient. In my experience over the past 37 years, these explanations almost inevitably aim to conclude with someone taking my money, dignity, or integrity.

Instead, I’m perfectly satisfied with those unearned, unknowable moments of cosmic synchronicity—where the moment is one of a thousand marbles encircling a foucault pendulum, and coincidence is the pointed tip of the bob that always and eventually knocks each marble off its stand, proving the rotation of the Earth and the predictability of patterns in one tap.

Depending on how long you’ve been watching and waiting to see it happen—to see the swinging bob strike a marble at just the right angle, after hundreds of near misses—the relief you’ll feel can make you float. You’ll move on with a sense of comfort and certainty as irrational as luck, and just as rewarding.

Excerpt #5

My friend and her husband had a mild confrontation with someone else soon after we’d gone on the nature tour. A man, his wife, and their two daughters wanted to take their dog down the bird trail. My friends recognized them as guests who’d come through the lighthouse on a tour earlier that week, and they’d picked up on a weird dynamic then too, between the man and the rest of his family.

“Is this for real?” the man complained, pointing at the signage that made it very clear he could be fined for disregarding the rules of the primitive zone. “We came all this way and we can’t go down there?”

“Oh really, how far? Where are you from?” my friends asked, trying to stay in friendly volunteer mode.

“About thirty minutes,” he said.

We’d come from Utah to be there, but it’s all relative.

“There’s a dog beach over there,” my friends informed him.

“But that’s not over there!” that man retorted, gesturing back toward the bird trail.

My friends explained some of what we’d learned about the reason for the rule, they tried to make conversation about the cuteness of their dog, but the man was unappeased and the women wouldn’t look at them, respond, or interact. They’d look instead to their husband and father, their eyes circling him—his emotions, his voice, his grievances—like marbles down a drain.

Excerpt #6

On our way back from Walmart, we found ourselves trapped in a current of a slow-moving procession of classic cars. The Classic Car Parade was only one of many events lined up for July 4th festivities that week, and its route looped all through the campground at Tawas Point State Park. Our routes overlapped almost to the door of our lighthouse. We were in it for the long haul, waving at spectators in our underwhelming, very modern rental, but enjoying the enthusiasm.

The man in front of us, however—a normie like us, but in a beat up black Jeep—wasn’t having the delay. At the first opportunity, he revved his engine and shot the gap at an intersection into the Park, cutting off the driver of one of the dressed-up classics.

Honking ensued and the Jeep driver brought up his middle finger as he continued through the narrow crossroad. Everyone who’d seen it shook their heads and made the faces that mean ‘there’s always gotta be one, right?’

The gap-shooter was still ahead of us when we made it through the intersection. We watched him pull into the parking lot by the public beach pavilion and jerk to a halt in a stall. He exited the Jeep and walked harshly toward the pavilion, as though in constant collision with the world in front of him. A handgun was visibly holstered above the waist at his lower back, between his jeans and his sweaty black tee.

That was when I decided not to confront another person about their dog on the bird trail.

Excerpt #7

“Is anybody here because their great-great-grandfather or great-great-grandmother worked in the camps?” he asked us. “Or came to live in Oscoda?” No one knew. He went back to his props, humming some more, sweltering.

When it was clear his crowd wasn’t getting any bigger, he introduced us to his gabriel horn, the long brass horn he’d trumpeted to call us to him. He said the horn was used to call the shanty boys to meals. Then he told us to close our eyes. We did. He told us to imagine ourselves back in time to the year 1870, to picture ourselves in the dead of winter on top of three feet of snow, and to imagine ourselves as nineteen year old boys plucked from obscure locales. Then he jolted us out of it by blowing the angel’s horn again. Our eyes shot open and we were stunned to see he’d blown the horn directly into a woman’s ear.

She’d been closing her eyes like the rest of us, playing along, while he’d sidled up, pointed the flared bell of the three-foot horn at her head, and emptied his lungs into it.

Was it to drive home the brutal shock the shanty boys must’ve felt on their first day at the camp? Or was it a covert assault on an older woman? He moved on with the presentation so quickly, no one really knew how to react, including the woman with a probably ringing ear. But I personally registered a discernible loss of good will toward Michigan’s more clownish, less talented Michael Gambon.

Excerpt #8

Didn’t I realize I was killing them? These filter-feeding passive killers of fish? The only reason they were there, decimating the hatcheries, was because of us (humans), carried over in the ballast water that stabilized ships following transoceanic routes.

But zebra mollusks don’t have the expressive eyebrows of my dog. I couldn’t personify them. We had no history together. Worse than strangers, they were objects, brittle hulls shattering under my deliberate, unfeeling weight. A sound and a sensation.

Crunch.

I break the same rule every time I order a Wendy’s Jr. Bacon Cheeseburger—the rule I’ve given myself to empathize with all things, all people. As much as possible. So long as I’m not too angry, hungry, or threatened, that is. I’ve seen the movie Okja and have read the first few chapters of The Jungle by Upton Sinclair, so I chew through the assembly-line-slaughtered pig and cow flesh with a guilty heart, “the hog-squeal of the universe” ringing in my ears.

Excerpt #9

We talked to Housewife’s Guilty Pleasure for a while, though we never did get his name. The dog, however, was Zupper. Zupper the Pupper. His hoppy little trot took on a new rhythm.

Zupzupzupzupzupzupzupzupzuozuozuozuozzupzupzupzuzpuzupzupzupzuzpuzpuzpzu

As Zupper zupped around us, the man said he’d rescued the poodle from the home of one of his elderly clients. He was a contractor who did work in people’s homes, and he was the one who’d found the body of Zupper’s previous owner.

“They were dead when I got there,” he told us. “Been dead for thirty hours at least.”

His voice was a benign growl, like the rasp of coarse-grained sandpaper across a plank of Michigan pine. I could imagine him recruiting shanty boys with that voice.

“Natural causes,” he assured us, saying Oscoda had no crime, and that he never had understood the appeal of crack anyway. All that for a two-second high and money down the drain.

Poor Zupper, trapped in a room with a dead body for thirty hours. The man had been taking care of him ever since, and now they prowled the beaches of Oscoda together picking up chicks.

Zupzupzupzupzupzupzupzupzuozuozuozuozzupzupzupzuzpuzupzupzupzuzpuzpuzpzu

Excerpt #10

In 1850, Tawas Bay was a pretty peaceful place. There existed a few log cabins, a few hearty fishermen and farmers, and a tribe of Chippewa Indians led by Chief O-ta-was … Local history states that Chief O-ta-was was a frequent visitor and dinner guest at the lighthouse.

This is an excerpt from an article in a paper produced by the Friends of Tawas Point Lighthouse. We didn’t find much written about the native people of the area in provided study materials, so any mention jumped out, including any detail hinting at peaceable coexistence. That never is the full story, is it. The full story is zebra mollusks, and the slow and inevitable crushing of native species, but doesn’t it feel nicer to tell the one about the dinners?

“Who knows where the name ‘Tawas’ comes from?” we’d sometimes ask visitors. We’d mention Chief O-ta-was, but without knowing more about him, there wasn’t much else to say.