On Weirdness and Play: Or an Ode to the Creative Haven That Was My Uncle’s House

I was in the second grade, a couple weeks into the school year, when the bell rang for recess. We all lined up (as trained) to leave the room in an orderly fashion. As I waited for the line to start moving, I asked the teacher about something that had begun to bother me:

“When are we going to get homework?”

We were far enough into the school year now that Homework’s failure to appear had started to feel like an oversight, and my tone must have suggested as much—likely needling and obnoxious.

“When are we going to get homework?”

I stared up at her with a probably drifting eye, probably long tangled brown hair, maybe even wearing the XXL shirt with the giant printed cow on the front I loved so much around this time. And the way she responded has never left my brain in thirty years.

“You,” she said, “are a weird kid.”

I hadn’t learned shame quite yet, so I don’t recall feeling embarrassed as I thought, simply, She didn’t answer the question. I eventually understood she just wasn’t going to for some reason, and then ran off to recess.

No Miss Honey, this woman, but I don’t remember her as Miss Trunchbull either. That was my third-grade teacher. I wouldn’t meet Miss Honey until the fourth grade—the teacher who first introduced me to the idea of “writer” as a profession and identity.

Today I try to imagine how I might have looked and sounded to her—my second-grade teacher—to have responded that way to a child’s totally answerable question. She must have found me comical at best, annoying at worst. But the reason I wanted to know when we were going to get homework wasn’t precisely because I couldn’t wait to do it. It had more to do with wanting to know what kind of homework we were going to get in my new grade.

Was it still going to be little-kid homework delivered on blurry-blue-ink printed worksheets, or was it going to be big-kid homework on thinly lined paper with a textbook?

My question may as well have been, “Are we big kids yet?” But what kind of response would she have given me to that?

Probably about the same.

“Child’s play” is supposed to mean easy, practically frictionless, or even insignificant. But returning to unashamed weirdness, which I think is a prerequisite for play, has proven to be one of the harder things I’ve done as an adult, and the most significant.

The Inexplicable Shame of Adolescence

In three more years, I’ll enter my 40s, and it feels like this: My mind’s finally coming together as my body falls apart. My knees have crunched since I was a teen, but injuries healed faster then, and I could sprint without breaking finicky little hip bones. The tradeoff, of course, was that I was a teenager—a big kid who had learned shame at last, and was, to my memory, still weird.

Being weird with a shame-based mindset versus being weird with lizard-brained resilience to external judgment is a wholly different experience. I liked being a kid; I hated being a teenager. Sure, I’d wanted to grow up and get access to all the things my age had denied me—information, media, jokes that went over my head, homework with textbooks and lined paper—but my teen years could be summed up in the words of Switch from The Matrix right before their death: “Not like this. Not like this.”

I’m surely not alone in remembering my teenage years with a cringe, but did it also seem to you that most of your peers were simply having a better time? All’s well that ends well, I guess, but I wish I’d had a better perspective as a teen. I think I could’ve had a lot more fun, but angst put me solidly in my own way.

I believe when we age into access, we age out of a dauntless capacity for bliss.

I was perpetually mortified by my changing body, depleted of self-esteem, and convinced of a personal tendency toward faux pas. Eye contact was interrogation and attention of any variety felt like the Eye of Sauron, even while I craved to feel seen. A contradiction and a conundrum, I didn’t make sense to myself, and I’d developed a specific anxiety that my life had never been—and would never be—mine.

In short, I’d lost the knack for living happily, or at least boldly, as myself. Reading, writing—even dreaming—became escapes I looked forward to. As a teen, they were some of the only ways I still “played.”

The Sublimity of Play

I believe when we age into access, we age out of a dauntless capacity for bliss. In Upstream, Mary Oliver writes, “It lives in my imagination strongly that the black oak is pleased to be a black oak.” In this way, I imagine a black oak like a toddler, even with their inability to regulate emotion. Their rage is rage and their joy is joy, unadulterated. They simply are, having arrived in the world without any choice in the matter to be affected by decisions already made, but with an instinct for play as true as the black oak’s instinct to pleasantly abide and grow. In both I see the sublime.

“Who knows when supreme patience took hold,” writes Oliver, “and the wind’s wandering among its leaves was enough of motion, of travel.”

In play as a “weird” child, I’ve traversed dimensions and had adventures reminiscent of Gulliver’s travels or Odysseus’s odyssey, two stories I became fascinated with at an early age (the 1996 and 1997 movies respectively). Both are eerily captivating globetrotting and discovery tales. Watching them again today would undoubtedly transport me somewhere. But that’s what I’m after. A transportation, or a return to the Bekah who’d been called weird but didn’t feel the implied shame.

“Child’s play” is supposed to mean easy, practically frictionless, or even insignificant. But returning to unashamed weirdness, which I think is a prerequisite for play, has proven to be one of the harder things I’ve done as an adult, and the most significant.

It lives in my imagination strongly that the black oak is pleased to be a black oak.

Mary Oliver, Upstream

A Special Home for My “Weird”

My uncle’s house was where I found a special home for my “weird,” and where I learned a precedent for play that continues to set a standard for how much fun I can have when I let my inhibitions go.

I spent more time at his house than at any of my parents’ other siblings’ houses, especially once I was able to start driving myself the familiar route from Orem to Lindon, Utah, because one of his daughters was my best friend and writing partner through junior high and high school.

I loved being there; I didn’t feel isolated in my weirdness, because my cousins were boldly, deliciously weird.

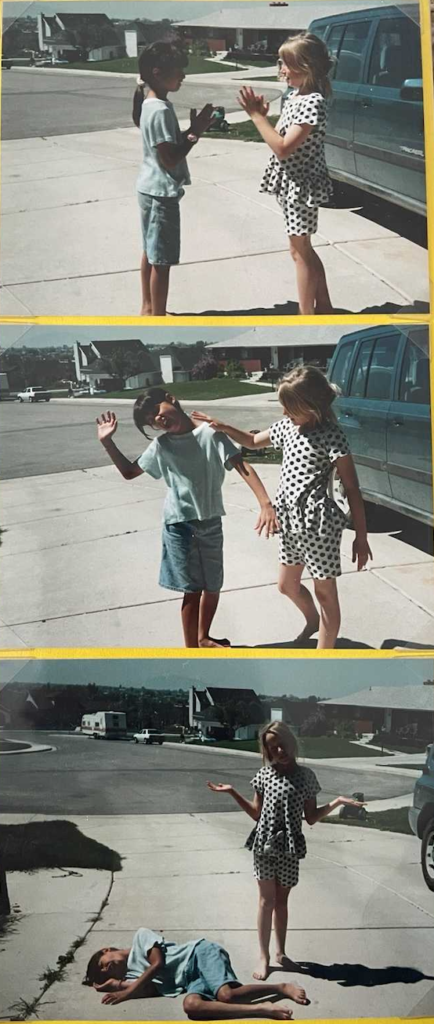

Exhibits A through C:

- Their fights contained strangely legalistic and advanced parlance for children: “You’ve been harassing me all day! Stop harassing me!”

- Doritos chips were used like currency: “I’ll pay you ten Doritos if you do my chores today.” Whoever managed to get their hands on a whole bag ruled the house for as long as they could manage not to eat their fortune themselves.

- And they made each other nachos as either apology or a bid for karmic balance: “I made you nachos so now we’re even for me burning you on purpose with the curling iron.”

As for the fun we’d have, our Barbies had narrative-driven adventures with drama, twists, romance, and adventure. I learned a love for Les Mis at my cousins’ house and together we belted out songs from the soundtrack at the piano and around the house.

We filmed ourselves doing skits, spent hours playing jumping games on the trampoline, and tied the corners of blankets to our wrists and ankles to stand on the hill in their backyard when the wind was high, leaning against it like wingsuiters in training.

We played raucous rounds of Spoons, and a game played in the dark throughout the whole house called Red Glove. I don’t remember the rules, but there was a glove and a lot of chasing and running to the safety of couch to couch—and so much laughter, along with some broken furniture.

Most of the walls in their home were a shade of teal—it was like walking into a buttermint—and my aunt’s art and tastes were everywhere. Fancy dolls fashioned after her four children acting out “play” above the cabinets, a jungle themed master bedroom, every surface a canvas.

My uncle, my mom’s younger brother, was a pleasant, steady presence—a black oak—who mixed brown sugar with ketchup as a topper for the best meatloaf I’d ever had. A tall man, he loomed large in my childhood memory but unimposing, with Baloo the Bearish love for food and family. I ate many meals at his house, taking up a spot most weekends for a while at their dining table and always feeling welcome.

A tall man, my uncle loomed large in my childhood memory but unimposing, with Baloo the Bearish love for food and family.

Remember the curling iron incident? When one of his daughter’s deliberately burned the other with a curling iron as they jostled for space in front of the bathroom mirror in preparation for church one Sunday morning, I remember my uncle receiving the information with Baloo aplomb: “Well, that seems a little extreme.”

I rarely ever saw him angry, even upon opening the fridge and finding one of his favorite snacks devoured by his niblings and children before he could have any. “My cheese ball!” he lamented, but even he had to accept the every-man-for-himself reality of raising and uncle-ing a houseful of growing kids and teenagers.

He’s the uncle I allude to in my post Harnessing Words of (Dis)encouragement, and I credit him for inadvertently cementing my resolve to continue writing no matter the odds I’d ever find success as an author.

“Do you know what the odds are you’ll ever be published?” he’d educated me one day, probably after finding out how much printer paper his daughter and I had been using to churn out page after page of horrible-but-not-much-different-than-what-we-were-reading-at-the-time fantasy. The implication being we were wasting our time and his money.

I never gave myself the chance to resent him for trying to discourage me. He likely forgot his words by the time he fell asleep that night, but feeling forced as a child to confront the possible futility of a burgeoning dream probably changed the course of my life. I never stopped writing and now it’s how I make a living. It’s how I process the world and create my own. I can’t resent him for that. In fact, I realized this year how much I love the guy.

Feeling forced as a child to confront the possible futility of a burgeoning dream probably changed the course of my life.

If this is starting to feel like a 1700 word lead-in to a eulogy, I hadn’t planned it to be when I started this meandering essay. But Uncle Roger has been on my mind, and thinking about play led me back to the home he and his wife created on that hill in Lindon.

He passed away last month from an aggressive lung cancer at 67. A few weeks before he died, one of his daughters asked the family for messages and pictures to put in a book for him to have at his bedside. This is what I wrote, and how I’ll end this essay:

Dear Aunt and Uncle:

For a significant chunk of my youth and adolescence, your home was like a second home for me, a teal haven of creativity and fun. Thank you for always making room for me. I ate so much of your food! But I always felt welcomed and cared for. Play felt different at your house. It felt free and purposeful and real. You had an entire play room! Going up there felt magical—the stories and worlds we created could spring forth in a space specifically designed for them. Thank you for being the influence in my life I most strongly associate with purposeful play and creativity, and with joyful individualism. I love you both.