In Which I Explain to My Goddaughter (and Myself) What It Means to Have (and Be) a Godmother

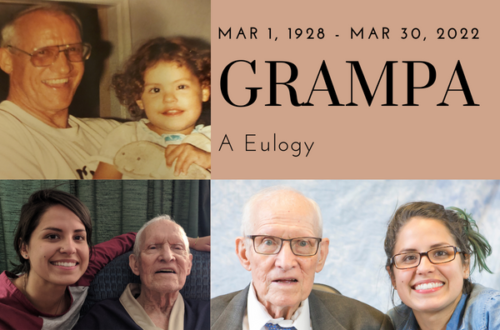

My dad had a godmother I never met. It wasn’t until we were working on The Music of Pedro together that I learned he’d even had one. He told me his godmother’s brother was the inspiration for a particularly scandalous plot point in the book. (I won’t spoil it. You’ll just have to read it.)

Growing up I never even heard of godmothers outside of fairy ones, and despite the solemnity and intimacy “godmother” suggests, what could that relationship have meant to him, or to her, if I’d never heard of her?

I called him as I started writing this a few days ago, and even though I called his cell phone, my mom answered as she usually does. Sometimes I wonder why Dad has a phone, or why my mom has two.

“Sergio’s secretary,” Mom greets laughing. No payroll budget in the world is large enough to cover what she’s earned in overtime alone.

What I Know Now About My Dad’s Godmother

It sounds like my mom takes the phone into the garage where Dad’s probably woodworking, and I have a brief conversation with both of them, even though she doesn’t put me on speaker. It’s just her relaying my questions and him shouting back answers for her to catch and repeat back to me, as the sounds I grew up with—wood-clattering, metallic dings, hammering—ring familiar in the background.

Her name was Rosa. He can’t recall her last name. She was a person of means in the neighborhood where he was born, who my grandparents thought was a good woman. He wasn’t her only godchild. I assume my grandparents weren’t the only neighbors to consider her an eligible candidate because of her social status. She would have signed the religious paperwork to make it all official at his christening, with the understanding she’d take care of him if he became an orphan.

My dad remembers his madrina—as he would have called her—as kind, but she wasn’t involved much in his life after he left Pihuamo (dubbed Pivámoc in our book) at a young age, or even when he and his brother did in fact end up in a sort of halfway house for children. His parents were still alive, but they surrendered him and my uncle to the care of nuns for some time when my dad was eight years old. (A story for another time.)

By the time he was an adult marrying my mom in the US, his madrina must’ve been little more to him than a childhood memory. But at least she was a bright one. She was kind to him. And after reading the preliminary drafts of his memoir, it makes sense to me that kindness would have made the greatest impression on my father as a child—on his hungry, often sad young mind.

Before we end the call, my mom mentions that his godmother wasn’t even included on her Christmas letter list. It struck me as a funny yet perfectly apt thing for her to add. That’s how perfunctory my dad’s relationship with his godmother had been, a standard protocol of a catholic birth. Or that’s how distant the memory of his catholicism had become. Rosa wasn’t even on the Christmas letter list.

A Brief Digression About My Mom’s Tradition of Sending Christmas Letters

It’s October, so Mom must have the letter on her mind. She’s maintained her Christmas letter list all her married life—a list of the names and addresses of everyone she wants to keep updated on the goings-on of hers and Dad’s cascadingly large family. It’s almost time to continue the tradition with “Cuevas Family Christmas Letter 2023.”

She sends them as emails now instead of physical letters, but she still tries to keep the letter to one page. Consequently, space in these letters becomes less egalitarian every year, with each 12-month span bringing new human additions or events in need of comment. What (and who) does and doesn’t get to be mentioned or discussed at length in these yearly updates becomes more and more subject to neighborly scrutiny and speculation.

Last year a cousin called me to ask why one of my six siblings had barely gotten a line of an update on their life. “What’s going on there?” she wondered. She also commented on who had edged into the limelight, ole reason-for-the-season himself: “Jesus got a whole paragraph.”

The question of who’s included on the list is easier now that Mom just sends a mass email, but Godmother Rosa hadn’t made the cut in the time of printing, stamps, and envelopes, so why would she be on the list now? She’s likely not even alive anymore, let alone checking an email account anyway.

It doesn’t surprise me that my dad chose to end the godparent tradition for his children. Having been converted from catholicism to mormonism at sixteen, my dad rejected, avoided, or just didn’t think anymore about holdovers from his catholic upbringing. Not enough to inject this particular catholic tradition into his children’s upbringing at any rate. (My sisters and I didn’t have quinceañeras either.)

Dad’s no longer catholic and his experience with the tradition doesn’t appear to have been particularly sentimental, but his experience is only one example of what the relationship can mean.

A Secular Approach to Godparenthood

When close friends asked my partner and I to be godparents to their daughter, the four of us got to decide what the relationship would mean to us. Like my dad, none of us are catholic, but unlike my dad, we’re not religious either. This makes the “god” prefix ironic, but we’re keeping it. The core agreement to raise her in the event of tragedy remains as well, but there was no baptism or formal ceremony.

There was, however, a ChatGPT-assisted godfather’s speech, and my own improvised words delivered to our friend’s ready-to-pop belly in their living room. It was agnostic, casual, sincere, and emotional, and in my partner’s case, predictably nerdy as hell. It’s a beautiful memory.

Before our most recent visit, I made a Shutterfly book full of pictures of me and my partner plus Kylo. It’s addressed to my goddaughter, and alongside the photos, I reiterate the promises we made to her before she was born. She’s six months old now and I read it to her while she was stuck in her jumper and had to listen. And god was it cute how well she listened. Here’s how it starts:

Tia—that's me—made this book for you. I'm your godmother, Tio is your godfather, and Kylo is our pup and your goddog. We all love you and hope this book will help you get to know our faces in between visits. I also want to tell you a little bit about us.

(Tia means “aunt” in Spanish; tio, uncle. While madrina/padrino would’ve been more accurate, none of my nieces or nephews call me “Tia,” and I wished that’d been more normalized. Also I wanted something a little different for this relationship.)

The next page explains how we hit it off with her parents:

Tio and Tia moved to California in 2017, six years before you were born. Tio got a job where Daddy worked. That's how we met your parents! We all became instant friends when Daddy and Mommy threw a Halloween party, and Tia and Tio demolished the competition in Harry Potter trivia.

***

I included family photos from our wedding so she can see pictures of people she’s now distantly and unconventionally connected to. I tell her how we found Tio’s dad and paternal family with a DNA test, how we were overjoyed to have found him in time to become friends and invite him and his wife to the wedding.

“Families can grow in all sorts of ways,” I say.

I share pictures from Kylo’s puppyshoot along with a glimpse into my love of words:

When Kylo was a puppy, my cousin and I had a lot of fun doing a baby photo shoot with him. I was very excited to have a puppy and Tio and I treat him like a son. He's our dogson! We love having a dogson and a goddaughter, because that makes us dogparents and godparents and wordplay is fun!

***

And finally, I come to the promises and explanation:

I want to tell you a little bit about what it means to be our goddaughter. Remember how I said families can grow in all sorts of ways? This is one of them! We’re basically an extra set of parents for you! And as your godparents, we promise to help Mommy and Daddy show you all the love, guidance, and help you'll need as you discover the world for yourself. You're our goddaughter! We're excited to get to know you more and more every year, make memories, tell jokes, and talk about life and space and happiness, or whatever you want to talk about. You’ve been born into a beautiful world full of incredible things, but it can also be confusing, alarming, and sad sometimes. That's why it helps to share the journey with others! We're here to answer questions, learn alongside you, offer comfort and protection, and just help you out in all the ways we can. [Goddaughter], we're excited to watch you grow and become your own person with interests, talents, dreams, and questions. We love you! And we'll always be a phone call, text message, email, road trip, plane ride, or stone's throw away whenever you need us.

What Being a Godmother Means to Me Plus Some Thoughts on Infertility

***

I wrote the little Shutterfly book to help our goddaughter get to know me and my partner, and to articulate a commitment I take as seriously as staying current on my birth control, or simultaneously, as seriously as the likelihood I accepted a long time ago I wouldn’t be able to get pregnant if I tried. In other words, birth control has probably been a moot point since before I started having sex, but I’ve never felt inclined to take the chance it wasn’t.

Interestingly, considering my own likely infertility, my goddaughter’s conception required medical intervention. Intrauterine insemination, or IUI.

“Basically my husband jacked off into a cup and they shot it into my cervix with a tiny turkey baster,” says her mom. If that doesn’t put you in the mood for Thanksgiving, I don’t know what will.

My friends put in more than the typical amount of effort to get their baby here, and I received the invitation to godmother their child as a compliment and a gift. Families can grow in all sorts of ways, and I love the path that mine is taking.