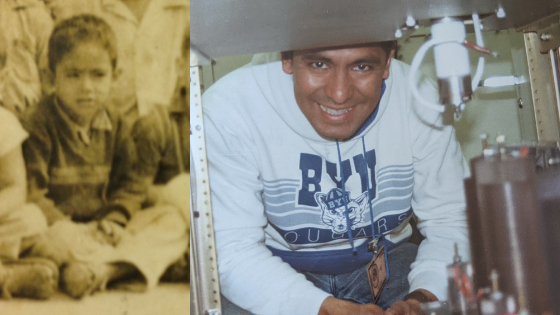

From Mexican Child Laborer to Civilian Engineer for the U.S. Department of Defense: An Interview with My Dad on the Eve of His Retirement

My parents are taking me to the train. We back out of the driveway and get a view of the house they’ve been living in since 2012. It’s the biggest house they’ve ever owned. Vaulted ceilings, almost a full acre lot, plenty of room for their thirty-four children, in-laws, and grandchildren—and five dog-grandchildren—to gather together at once. It’s a pretty house, cross-gabled, red brick and stone, an expansive view of the mountains off the big backyard porch.

“It’s all yours now,” I say. They paid it off three months ago, an accomplishment that always bears repeating for the way it makes them feel.

“This was my dream,” says my dad—his own land, a house full of food and loved ones, permanence. His childhood was punctuated by all the places he’d had to leave for want of money.

He retires in a week. I’ve written his last day on my own calendar because I’ll have a full month of living with him and my mom afterward, before my own house is finished. I’m excited for the possibilities his time will hold once he’s finally finished using it all to subsist and then decompress from the emotional strain of it. He says what he feels most at the prospect of retirement is the relief of leaving behind the social navigations of a work environment.

“I like people,” he says, “but not people who make your life hard.”

My dad likes to be liked. So do I. So do you, probably.

“There are some people who won’t like you from day one,” he says. “They choose not to like you.” He says it’ll be a relief not to deal with these people anymore, at least not forcibly. He’s excited to spend his retirement years with people he’ll get to choose.

I’m glad he and my mom have chosen to spend these past months with me, LT, and Kylo. They’re letting us live in the basement while we wait for our closing date, and even Kylo has settled in so comfortably that he’s developed the routine of listening for grandpa’s footsteps upstairs every morning—his cue to run up for good-morning scratches before grandpa leaves for work. One night I’d closed my bedroom door and my dad noticed Kylo’s absence the next morning.

“Why didn’t Kylo come up to say goodbye?” he asked when he came home from work that day.

Another night, after playing a board game with me and LT in the basement, my dad made sure the basement door was open a crack before he left upstairs for bed. “For Kylo tomorrow,” he said.

Decades ago, we bred a couple of litters of wiener dogs. Sometimes we cordoned off the puppies under the kitchen table with upended benches as barriers to hold them in. When my dad came home from work, he’d lie under the kitchen table and let the puppies swarm him with their frantic, unquestioning love. He’d just lie there, unwinding from his day.

***

We arrive at the train station. My dad holds Kylo’s leash as I tote my weekend bag. I position my mask before boarding and Dad hands me the leash. We say our goodbye-for-nows. He and my mom are off to Costco and I’m on my way to see LT then spend a few nights in a Sundance cabin with a small, mostly vaccinated or immune group of friends.

My plan is to use the time, the scenery, and the company as impetus to stew over the recent conversation I’ve had with my dad about his upcoming retirement. I’d prepared questions for him but kept postponing the “interview” until one day after work he sat down on his recliner and just started talking. The iron was hot.

“Hold up,” I said. “Let me grab my laptop.”

Since moving in, Dad’s routine has been “wake up, work, come home, watch Star Trek, bed,” as my mom warned me it would be. He’ll do more on the weekends, even play board games sometimes, but I recognized Star Trek binging as a post-work weekday necessity, like the puppies had been decades before.

Path to Becoming a Retired Engineer

What was your very first job? The first thing you did to earn money.

I worked in the sugar cane fields at eight years old. One peso per day, I think, for six hours of weeding the rows of sugar canes.

(I heard this story for the first time while working on The Music of Pedro with him. He worked with his brothers to help pay for the partera who would deliver his baby sister.)

What was the first thing you ever bought for someone else?

I would give money to my mother, then she’d give me 25 centavos at the end of the week, which I’d use to buy a concha.

(In the book, conchas—sweet bread—is the food Dina loves the most. Today my dad makes Portuguese sweet bread—or chi-chi bread as we call it for its ample, breasty quality—almost every Sunday as a gift for his neighbors or coworkers.)

What was the first thing you bought for yourself?

Food.

What was the first thing that was gifted to you?

It was a little plastic tank that shot plastic bullets with a spring. Before I finally got it, I asked niño dios—baby god—for anything. Bring me a gift. But I got nothing. The next year, I asked the magi kings. But every time I didn’t get a gift. Then I wrote to the gringo Santa Claus. That year I got the tank. I was five years old, I think. In the morning, I tied a string to the tank and went outside to show it off to my cousins. I was dragging the tank behind me and one of my cousins jumped off the windowsill and smashed it.

(As kids, it became a Christmas tradition every year for the Cuevas children to hear this story so that we’d better appreciate our gifts.)

Describe your work history.

From the sugar cane fields, the next job to support the family was to learn how to sew to help my mother make pants and shirts. We’d get the material from a Jewish family in Guadalajara. It would already be cut up and we were the ones that sewed it for their stores and they’d pay us.

My mother had a Singer machine and taught me how to sew so I could help. At this time, I was around twelve years old. We decided to keep on sewing, but we would buy pieces to sew and sell door to door. People would buy them because we sold them cheaper than in the store.

I kept going to school and would get very good grades. I wanted to be a learned man and would study hard. At this time, I was now fourteen and I saw that people had little grocery stores everywhere. People would go to these stores to buy eggs a lot. Everybody used eggs, so I went directly to the farms to buy eggs directly from them. I bought a box of 365 eggs and went door to door to sell them. These were fresh from the farm, I went to your house, and they were cheaper than you could get them from the store. Everyone bought my eggs.

I calculated how long it would take for my customers to use up the eggs and then created zones. I staggered the zones I visited so that by the time I visited the last zone, it was time to return to the first. This gave me reliable clientele and a steady income. I got my brother Ramon to help and then expanded the zones. We started to make a little living out of that and still be able to go to school. Ramon liked to play basketball and got bad grades. We were in the same grade together and he’d listen to me study instead of studying himself.

From sugar canes, sewing, and eggs, to chickens

I started wondering if I could make more money selling chickens than eggs. Two of the farmers I bought eggs from were gay men. I asked them, “Can I make more money selling chickens than eggs?”

“Yes!” they said.

“How do I raise chickens?” I asked.

They told me that they would be ready to be sold for meat in two months, but they needed to have light all day and to eat all day and night and to be kept clean.

The gays like me. They were very nice.

(The business he started after employing their advice still exists today.)

I started raising chickens then rented a little booth at the market. At the beginning, I would have the chickens in my bedroom and I slept in the corridor. A hundred to two hundred chickens would fit in there. I fed them Purina and they grew fast. Then I sold them live at the market. I’d weigh them alive then kill, defeather, and chop them there. Eventually the whole family helped with that. I stopped selling eggs completely and sold chickens. We did that as a family until my father became a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints and stopped leaving us. I sold the business to my cousin and my father started woodworking.

By that time, I had an arrangement with the high school where I would study on my own and then only come in to take the midyear and end of year tests. I learned how to learn from books, and I liked giving myself assignments. Every time I took the tests, I would get the highest grades and get field trip prizes to go to the ancient ruin sites in Mexico. I did it this way so that I could have the time to work and feed my family.

When we were doing the chickens during the day, my mother started a restaurant at night. Posole, enchiladas. We had a little post in the corner across the street from a bordello. In the restaurant, two things happened: my mother didn’t want my older brother to go to the bordello to feed the prostitutes and drunkards because he was older and more handsome. So I would go, and one time there was a big fight and the bouncer grabbed me and took me outside to save me. I was fifteen at that time. Then, one time there was a murder a half a block away from the restaurant. We saw things, but the next day, before the judiciales came over, someone came over from the bordello to warn us not to say anything or we’d be in danger. We kept quiet.

From chickens and restaurants to woodworking

It was after that, that my father became a member of the LDS church. We stopped the restaurant and chickens, because the church gave us a contract to make all the furniture for the distribution center in Mexico City. We started making doors and rented a shop to become a carpinteria around the corner from home. We sold to universities and house contractors, but the church contract was the biggest one we had. We made everything: shelves, bookcases, doors, desks, everything the distribution center needed. Then we started furniture for stores, and living room sets. We made the skeletons for couches, then beds and spindles. We paid a guy who taught us how to lathe and showed us how to make our own lathes.

I developed ways to make our processes faster. I encouraged my father to buy a machine to help with some of the processes. Instead of staining by hand, we dipped our pieces in a big vat. Instead of buying wood from retailers, we moved the factory to the foot of the mountain to be closer to the wood to get it cheaper. Then we processed the wood right there. The business lasted until after my mission.

When did you know you wanted to be an engineer?

Before I even knew what an engineer was. My love for engineering came when I was a little kid in Pihuamo (Pivamoc in The Music of Pedro). Because of the mining that was done there, we had a lot of engineers come to my Tia Eva’s restaurant (Ana’s restaurant in the book). She would have regular customers. They would pay her every week for breakfast, lunch, and dinner all week. She was a very good cook. They were mainly engineers. My madrina (godmother) had a big house with rooms all around and would rent the rooms to the professionals, who’d eat across the street at Tia Eva’s restaurant. I was drawn to them. They seemed intelligent and well educated. I didn’t know exactly what they did, but I liked how they talked and dressed, and the fact they had money for all the food they wanted. I knew they were called “engineers,” but it wasn’t until high school that I learned what engineering was.

Describe your work history after you immigrated/became an engineer.

A couple of weeks after my mission I went to BYU. Even though I never graduated in Mexico, I passed the SAT to be accepted. I worked as a custodian then I left that because a friend needed a cook outside campus, at El Azteca. After that, I got married and started to work as a lathe operator at Rustic Interiors. I worked there a year before graduation until I got a job as a computer programmer at Geneva Steel.

My first graduate job was as an electrical engineer working for the Department of Defense. We spend 11.5 years in Ridgecrest then I came back and worked at Geneva Steel as a computer programmer again. From there to OEC medical systems as an electrical engineer. Then it became GE OEC Medical Systems and from GE I learned Six Sigma methodology for manufacturing continuous improvement. From there, I became a manufacturing engineer as a Six Sigma Black Belt. I used my skills in manufacturing processes to improve the manufacturing process for any company I worked for. Then to Intelliserv, from there to Chromalox, and from there to UST doing the same thing until now.

Describe your professional growth.

I made the leap into manufacturing due to my natural talents in seeing how to do things better and faster and more economically. With all my professional experience and opportunities for training, I was able to complete a set of tools to make my talents flourish, and I felt more confident having all of that under my belt.

By being exposed to hard work at the beginning, I was never afraid of work. I got my hands dirty and tried new designs. Though a lot of problem solving feels like bluffing, I felt confident that the results of any new system would be as I designed them to be.

I had to anticipate ways to make myself more valuable and make choices. When things were going wrong at a job, I had the opportunity to go get training. Although some managers would say it was a waste of money and time, I would prove that it was beneficial to the company. These trainings became useful for the next job, such as my training in Six Sigma.

Chromalox was the first place that saw my worth. I did a lot for them, changing the whole layout of the manufacturing floor to increase production by 400%. For example, I instituted a single-piece flow for one of the lines instead of a batch mode, which resulted in building one unit every fifteen minutes takt time, with four stages of assembly (15 minutes each). The total time to build a single unit with my single-piece flow was one hour, instead of four hours with batch mode.

Describe obstacles that you’ve encountered in the course of your career.

My main obstacle was human. People refusing to change. There’s a technique in Six Sigma where you involve people in the decision to change, which helps. But it wasn’t just trying to get people to adopt new processes, it was having to work twice as hard to get the same amount of respect as my peers. Though I was a senior engineer, I was often not treated as a peer.

What are your post-retirement plans?

To finish my second book and to get the Spanish version of The Music of Pedro ready. Maybe I’ll do children’s books later on. I want to go fishing. I want to go to Hawaii. Then England to take your mom to Steeple Ashton. I want to help my grandkids learn skills, woodworking, farming, chicken raising. I want to encourage education and reading. I want them to develop their talents. I want to do what I wish my mother and father had been able to do with their kids.

Reaching the Finish Line

A few days ago, on a weekday evening, someone drove into the parking lot at my dad’s work and fired three shots at one of the buildings. My dad was home from the office by that time and no one was harmed, thankfully, but one bullet passed through a window three inches from his colleague’s head. It’s being investigated as a murder attempt. Just one more reason in addition to Covid that his last day can’t come soon enough for any of us.

But he’s also been coming home with gifts this week—a new wallet, a Bath & Body Works gift bag, an assortment of baklava. Goodbye gifts from coworkers. He will be the first to retire from his current employer and they want to have a sendoff for him. I’m happy for it, these gestures of appreciation for a man who’s been working almost his entire life, who’s had to put an inordinate amount of effort—in my opinion—into winning people over through the course of his personal and professional life.

There’s a scene in The Music of Pedro in which Pedro fishes with his cousin on the banks of a river. They make their own rods and dry the fish under the sun. My dad did this too as a boy, but now he hasn’t fished in eight years. Today his neighbors who love to fish but hate eating them deliver their catches to my dad, who cleans them in the laundry room and dries them in a dehydrator instead of under the sun.

My aunt and uncle sent him a fishing rod yesterday. I’m excited to see him go full circle from the little boy who caught fish from the river with a homemade rod and dried them in the sun to a retired old dude on a boat with a shiny new reel.

8 Comments

Anne Marie Pace

What an incredible story! My husband and I were honored to serve with Spencer in the Spain Barcelona Mission. That’s how I noticed this FB post. Here are my observations:

1. Your father is very intelligent, a very hard worker, and very insightful. But most of all, he’s sensitive and compassionate. He never ever lost sight of who he is in times of poverty or in times of prosperity.

2. Your father and mother have very amazing children who are also gifted and talented and holding on to their inner identities.

3. You are a beautiful crafter of feelings via words. As a voracious reader, you are the word artisan I am always on the hunt for. I will read more of your work.

4. No wonder Spencer was so effective and loving and hard-working in Spain!!! The apple didn’t fall far from the tree!

5. I’d like to meet your whole family someday. Soon. I respect and love you all ready!

Reb

Thank you, Anne! Spencer’s the greatest. I’m glad you were able to find my post through your friendship with him. I appreciate your kind words so much and I know my dad will too when he sees them. If you’re interested in reading more, the book I mention in the post is up on Amazon in ebook form and print-on-demand, but we also have a few hardback copies left at my dad’s house 🙂 I’m sure I speak for all of us when I say we’d love to meet you too!

Sue Hart

Your father is an incredible man! We always felt that he was and now we know it <3 Thank you for sharing! We love you, Sergio! Congratulations on your upcoming retirement!

Reb

Thanks for reading, Sue! I’ll make sure my dad sees your congratulations!

Marcos

Your dad did so many things. Software engineering, electrical engineering, manufacturing engineering, and more. It’s so impressive. I’d love to meet him someday.

Reb

The day after he retired he cleaned out his woodshop and now he’s out there building cabinets for my brother haha. I’d love for you to meet, and for him to meet your parents too.

Leah Flake

I loved reading about this amazing man! I will always remember your dad for his incredible woodwork, big hugs, chicken knowledge, and cooking octopus (to list a few). He has made my world better, as it appears he has for many. God bless Sergio!

Thank you Bekah for recording and sharing. That takes a lot of work! These memories are so precious to have on record for your family.

Reb

Thanks, Leah! He’s a pretty special old chum, just like your pop too 🙂