Sleuths of 642 South: Ode to Hyperbole and a Half

One of my favorite blogs of all time is Hyperbole and a Half by Allie Brosh. Her book was assigned in one of my creative nonfiction courses and I chose to emulate her style for a later assignment.

Brosh pulls from a well of skill to share personal stories via drawings in Microsoft Paint and a little bit of text. Following suit, I picked one of my own childhood memories and I prefaced the story with this description of Brosh’s frolicking style:

Brosh’s artistic skill is so understated in her simplistic drawings, but there’s method and attention in every apparent scribble. She deals with nuanced and existential subject matter as well, which is made all the more meaningful and impactful when juxtaposed with her playful etchings.

I tried my best to mimic Brosh’s style in “Sleuths of 642 South.”

***

I have decided that cul-de-sacs are to children what socks are to feet. There is a nestling aspect to the half-looped concrete and inner circle of asphalt that murmurs promises of safety and coziness.

Cul-de-sacs lock in the familiar and delete the strange. What a child can’t see out her front window might as well not exist, so she doesn’t have to worry about it. And what I could see out my front window as a kid was the front of sweet old Sister Gammon’s mirroring red brick house with its towering walnut tree and groomed lawn.

Our shared cul-de-sac was abutted by a privacy fence that neighbors filtered through every Sunday to get to the giant red church building on the other side. I became accustomed to recognizing every face that wandered through my cul-de-sac so I reacted with suspicion to any out-of-the-blue mug that trespassed into my encapsulated world.

I imagined that I could see the outer world’s frightening mark on any face I didn’t know and felt certain that they weren’t just lost or taking the shortest route to a destination; they were up to no good.

I was at the age of the D.A.R.E program, so strangers were also obvious vehicles for drugs.

Now it might seem that this story, given the title, would lead to a Harriet the Spy adventure in which an overly suspicious 3rd grader equates an unknown face to probable cause and stalks a stranger for a block or two, but it’s not. It’s about a child’s love for encapsulation.

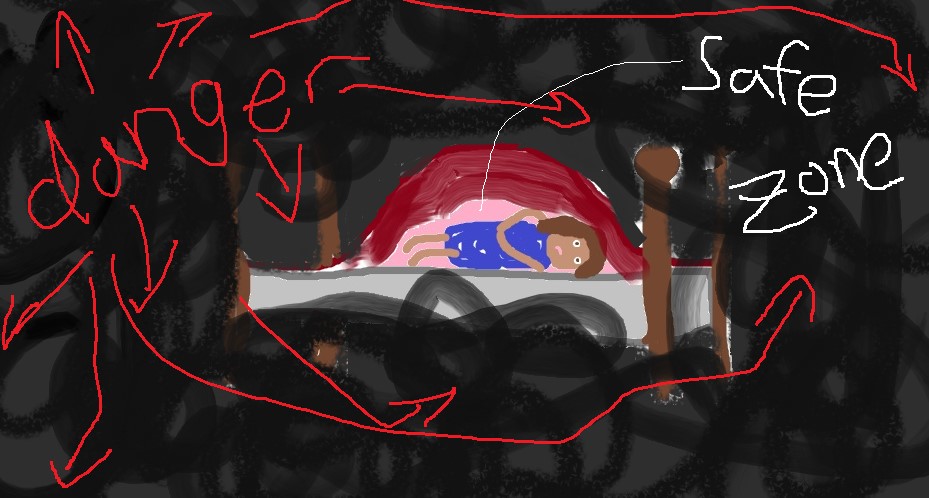

I liked my cul-de-sac for the same reason I made sure all of my appendages were entombed in blankets before going to sleep at night: because exposure meant being vulnerable to the specters in the dark. There was something about total coverage that inspired, if not courage, then a sense of peace.

So when my little brothers and I came into possession of two woolen, Sherlock Holmesian-trench coats by some interfamilial hand-me-down means, it was only natural that the three of us would put them on, plus one normal coat, and then proceed to cover the remaining inches of our bodies with boots, gloves, scarves, and hats so that only our eyes were visible.

Larry and Curly followed my lead, as it was all my idea and I hadn’t given them the option to do otherwise.

Throughout my childhood, my mother called us the Three Stooges. I was Moe, the oldest, bossiest, and the most brutal. If I wasn’t forcing my little brothers to comply with my psychosis, I was punching their xiphoid processes, dressing them like girls, or hacking Gap slogans to mock their teeth. At six, Curly told a dentist that his sister rapped “Fall into the Gap, Curly’s gap!” mercilessly often.

I was an impulsive and ruthless child who loved the feeling of being hidden in plain sight.

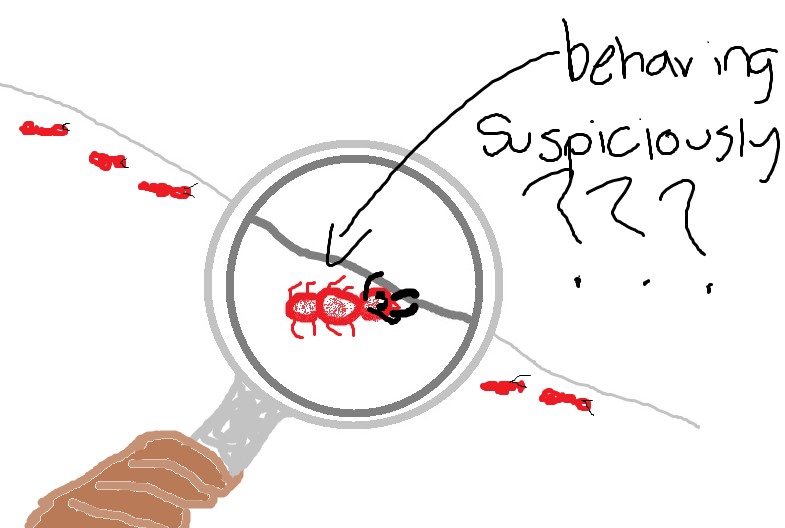

At that age, I was also an enthusiastic fan of Encyclopedia Brown, so the plan was to journey outward, beyond the walls of our house, even beyond the cul-de-sac, and to gather clues. We had a magnifying glass and a notepad for just that purpose. The only thing we were missing was an actual mystery to solve.

Off we went, venturing through the privacy fence and onto church grounds. We roved the foliage, investigated broken twigs and bugs, and etched notes like “black car in parking lot” and “leaves on sidewalk.”

We were really onto something, a real open and shut case, that one, until—

—we rounded a corner and came upon a pack of Sandlot-ian boys on bikes who looked appropriately surprised to see us. I recognized one of them from school, from my grade even, and understood that he was one of those awakened kids.

Girls liked him and he probably liked them too. And there I was, notebook of clues in hand, with my wide brown eyes peeking out through a gap in my tightly wound scarf. I felt a euphoric rush as I turned and fled, screaming merrily. Larry and Curly followed, screaming too.

We ran back to the cul-de-sac and back into our house, and I congratulated myself that the boy on the bike hadn’t seen me. Oh, he’d probably recognized me, but he hadn’t seen me at all.